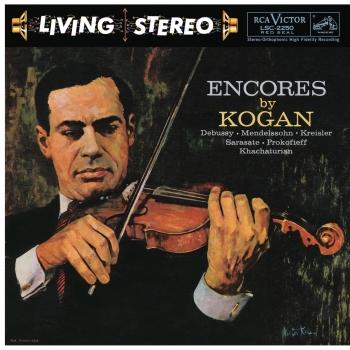

Leonid Kogan

Biography Leonid Kogan

Leonid Kogan

Born in humble circumstances, Leonid Kogan began his violin studies in 1930, encouraged by his father, an amateur player. He received a full academic education alongside a rigorous musical programme which included three hours’ violin practice every day and study of all the major violin methods of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as well as that of Carl Flesch. Kogan’s prowess is evident in his early success in the 1937 Ysaÿe Competition, even triumphing over many powerful rivals simply for the opportunity to compete outside the USSR. In 1941 he made his orchestral début with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, followed by solo débuts in Europe and the USA in the 1950s.

Kogan fell under Heifetz’s spell but, unlike many imitators of his style, added to it his own rigorous and distinctly Soviet musical personality. As a technician his use of the Auer-derived bow grip was notable, his powerful hands giving him immense poise and presence and the ability to execute very widely-spaced leaps with extraordinary precision and tonal connection. Playing for much of the time on a 1707 Stradivarius owned by the USSR state authorities, Kogan, unlike many, favoured an all-steel string setup (including steel-centre lower strings at a time when most players favoured a synthetic or gut core). This gave him a somewhat strident tone (certainly more so than David Oistrakh’s), although positive effects were clarity, brightness and power.

In spite of all of this, Kogan (unlike his hero, Heifetz) was prone to bouts of nervousness on stage. His best years were the late 1950s to mid 1960s. Latterly his tone deteriorated, becoming susceptible to what Henry Roth has termed the ‘on, off’ vibrato heard with many players from the USSR.

Kogan’s Bach recordings, represented here by the Sonata BWV 1014 from 1947, may seem a little quaint to modern ears attuned to historical approaches, but are also carefully sculpted. The Sonata’s slow movements in particular are beautifully sustained, showing a clear sense of reverence even if there is little evidence of the then-emergent scholarship into eighteenth-century practices. The allegro second and fourth movements hint at an almost infallible technique and, whilst both err towards a monumental Bach style, there is much to admire.

It is in twentieth-century repertoire that Kogan really excels. Shostakovich’s Concerto No. 1 under Kondrashin from 1966 equals Oistrakh’s supreme mastery of this, his friend’s work. It is a little more angular, almost mechanistic in outlook, lacking Oistrakh’s nostalgic softness beneath the dark, impassioned exterior. Technically it is sublime.

Kogan recorded both of Khrennikov’s violin concertos and his 1959 première recording of No. 1 shows the same brilliance of passagework as the Shostakovich, his trademark biting tone contrasting with lyrical sweetness in melodic sections.

Also included here is a fine 1966 performance of Berg’s Violin Concerto which (in spite of some halting delivery at first) develops into a dark, menacing reading. There is an equally praiseworthy Khachaturian concerto from 1958 which, with its fast-paced outer movements, rifle-bolt accuracy and extraordinary stamina, could not be in greater contrast with Mischa Elman’s faulty attempts at it from a similar period. The slow movement shows Kogan’s rare but artful use of portamento. A fast, discreet vibrato creates a sweet yet penetrating tone.

Kogan’s somewhat premature death deprived the world of a first-class violinist and, in the estimation of many, left the USSR (after the death of David Oistrakh some years earlier) with a dearth of truly great players.