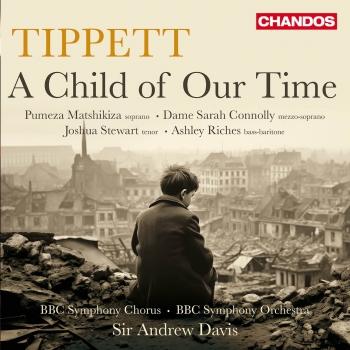

Chin: Cello Concerto Alban Gerhardt, Berliner Philharmoniker & Myung-Whun Chung

Album info

Album-Release:

2023

HRA-Release:

22.12.2023

Label: Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Concertos

Artist: Alban Gerhardt, Berliner Philharmoniker & Myung-Whun Chung

Composer: Unsuk Chin (1961-)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Unsuk Chin (b. 1961): Cello Concerto:

- 1Chin: Cello Concerto: I. Aniri09:42

- 2Chin: Cello Concerto: II.02:54

- 3Chin: Cello Concerto: III.07:25

- 4Chin: Cello Concerto: IV.06:35

Info for Chin: Cello Concerto

The music of Unsuk Chin is a magical realm in which new perspectives are constantly unfolding. Labyrinths of novel sounds and complex structures can be followed by moments of transcendental beauty. For us as an orchestra, this world poses certain challenges — indeed, it is part of Unsuk Chin’s style to test the limits of performing techniques. Or, to put it another way, she lets us show off our strengths. Her inventiveness exemplifies the inexhaustible vitality of today’s music. These qualities have made Unsuk Chin one of few composers with whom we’ve collaborated so frequently and productively.

About the work: For the four-movement cello concerto, Unsuk Chin was inspired by the “unique artistry of Alban Gerhardt”. The dedicatee premiered it in 2009 at the London Proms under Ilan Volkov and also presented the new version for the first time in 2013 under Kent Nagano in Munich. "The Guardian" described Chin's transparent work as "the most important cello concerto since Lutoslawski in 1970", which never obscures the soloist despite the large orchestral forces and richly explores the specific lyrical qualities of the instrument, despite all the technical difficulties.

Only very rarely does Unsuk Chin refer to the musical traditions of her native Korea. In the cello concerto there is actually a narrative anchor: the first movement Aniri is named after a term from Korean pansori theater and describes the narrative passages in these "one-man operas". And like the actor in an epic song, the cellist captivates everyone. It is introduced by barely audible, delicate touches from the two harps: they provide the central note G sharp, which is repeatedly used as an orchestral rallying point in the course of the movement and taken up by the soloist. Tubular bells and celesta are added, and the soloist's melodic line becomes more and more free. The spectrums between singing and noise are explored using highly differentiated playing techniques such as various harmonic degrees or hitting the bow stick on the string. The orchestra shadowily follows the cello, takes up a rhythmically concise figure, spreads a seductively glittering field over arpeggios and harmonic passages from the soloist - nine triangles support the impression of shimmering and floating. The short cadence leads back to the central note G sharp. The dreamy lingering is interrupted by an abrupt detonation - the orchestral extinction is mixed with improvisational, feverishly flickering impulses from the cello. With the instruction "as fast as possible", Chin pays tribute to the cello concerto of her teacher Gyo¨rgy Ligeti.

The frenetic, scherzo-like second movement was revised again after the premiere and its beginning was even composed from scratch. This sentence was "the only one that I had a very clear idea of at the beginning of the composition process. However, what came out at the end of the work was something completely different," said Chin before the revision. The soloist drives the action forward with motor drive, supported by the ostinato of the percussion. The strings' sixteenth note chains descend like lightning, played on the bridge with rich overtones. Unexpectedly in this rapid short ride, a melody enriched with artificial overtones unfolds in the cello, taking up Chin's original idea of writing a stylized folk song.

The following third movement acts as an extreme contrast and yet as if connected by a common exhalation and inhalation. This time the soloist establishes the central note G, around which a delicate chorale-like aura from the orchestra surrounds itself. With all its sensitivity, the cello spins out a chorale melody, accompanied by the low strings in a static, floating manner. After a culmination, the strings take up the chorale, then the woodwinds, accompanied by the cello in a dark contrapuntal countermovement. The ghostly end of the movement spreads out even more: the cello disappears into the highest harmonic regions, the gnarled contrabassoon descends to the earth.

After these spherical sounds, the orchestra gives the soloist a real blow in the last movement: hard chords fall on him, the sextuplet trembling of the violins attacks him, as a review of the premiere puts it, "like a swarm of hornets". The cello counters the incessant massive tutti attacks with searching, wandering figures. Unsuk Chin speaks of “psychological warfare”. After an explosion of orchestral colors, the cellist takes over the trembling, aggressive figure, until suddenly a long-winded melody, reminiscent of the Aniri movement, lights up again. The epic narrator doesn't let the collective get him down - he sings his soul unimpressed, accompanied only by a threatening motif from the double basses. The beauty in Unsuk Chin's music is always an endangered one. (Kerstin Schüssler-Bach)

Alban Gerhardt, cello

Berliner Philharmoniker

Myung-Whun Chung, conductor

Alban Gerhardt

Born now almost five decades ago into a household filled with music, I must say I was lucky enough of not having been pressured at an early age into making music too soon. Instead I heard my mother’s beautiful voice in practice and performance; I jealously interrupted my father’s quartet rehearsals; I heard—as a toddler outside of the church where Karajan always loved to record—all of the sessions for Wagner’s Ring der Nibelungen(perhaps why I’m not his biggest fan!); and I sat through several other operas and concerts of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, of which my father has been a member since 1966.

When I was four years old, my Dad tried to make me play the violin—an experiment which failed miserably not only with me but with all of my four younger sibblings. Frustrated by our father’s perfect command of his instrument, all of us got started with the piano, which I still think is the best way to “meet” music in practice. And one day, my sister Manon had just begun the violin experiment, my mother asked me if I was interested in playing another instrument besides the piano, and “how about the cello?” To get her out of my face, eight-year-old Me agreed, and my mother claims now that she could have named any instrument and I would have taken it on.

Although I didn’t think so at the time, I must now admit that I was very lucky with the choice of teachers from the very beginning. On the piano as well as on the cello, I had, with Wolfgang Saschowa and Markus Nyikos, two musicians who taught me the basics of my instruments, of practicing, and of music in general. The luckiest part of the beginning of my musicianship was the encouragment of my parents to work independently instead of being my second pair of ears. I was the the opposite of a child prodigy, went to school like everybody else, but I had one very useful talent: I had a excellent concentration which made me inspite of a rather normal intelligence a very good student. I finished Highschool one year early with the goal of being faster able to focus on my two instruments which used up already most of the day. Still I was able to become a big sportsfan (actively as a 1000m-runner with one German Youth-Championship, passively until today a soccer- and basketball-lover) and an obsessive reader of Russian novels (especially Dostoyevsky).

My first public concert happened on Feb.22 1987 in the “Berliner Philharmonie”, playing with an awful little chamber orchestra Haydn’s D major concerto. That means, I was almost 18 playing for the first time with orchestra. Why do I remember this date? I don’t know, perhaps because this day the hockey team of Berlin got into the First Bundesliga? Well, at least my father says now, that the news of this fact made me play better. Sad but true. This concert didn’t change anything in my dreams in wanting to become member of my fathers orchestra. A career as soloists didn’t even tempt me, since I wanted to have children and be a good father, besides the fact that I was not good enough by then. I started my studies in Berlin, went to Cincinnati for a year of intense chambermusic with the LaSalle and Tokyo quartets, and finally found in Boris Pergamenschikov the teacher I needed to improve one of my weaker spots: sound and projection. With his help I improved them and managed to win some competitions, national as well as international, which gave me the chance to start performing on a more regular basis. The national competition provided me with tons of little recital which made me realize that this is what I would love to do. Whatever stage, I loved to be on it and wanted to give the people everything at once, immediately.

A manager had even taken me on before any “official recognition”, which was rather daring but sweet from this man, and sooner than I could think I was having a little bit of a career. Sooner than planned came as well the big decision if to join an orchestra or not, since the principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonics was retiring early. My childhood dream was right there, but against my fathers and his colleagues advice I did not take the audition for the job. Not out of arrogance, neither the fear to loose, but rather the knowledge of my own lazyness convinced me that with 23 I was too young to be set up for life. I felt, I could still work much more and continue to try reaching my limits, which moved every day further and further away (they unfortunately still do), but that, once sitting in one of the great orchestras of this world and earning very good money, I would because of my own bad character stop fighting and working on myself. Besides that I had just discovered the joy of this incredible freedom as a free-lancing soloist, and I did not want to give it up sooner than necessary. I got lucky again, won a little bigger competition in the States and moved to New York.

I don’t even care if that helped the thing they call career or not, it just changed my view of many things, my entire way of thinking and playing music. Actually it showed me so clearly, how many totally different ways there are to make music, and that they all have their value, their lovers and their problems. The truth of each piece lays in us, if we manage to bring it to life, if we are honestly trying to tell the audience the story which is behind every piece, or if we just try to impress. And even the “just impressing”-part has a truth to it, because what else did Mozart do all his life than trying to impress some people who were so far below him, and the result is the work of a genius. It’s rather complex I guess, the search for the truth, but since it is such a challenge, it keeps even the 150th performance of a Haydn concerto interesting.

Just a little edit: After the US election 2016 and the Brexit Alban felt the need to become more engaged with what’s going on in the world, so besides taking care and housing an Afghan refugee he also became involved in the musician’s initiative “#Musicians4UnitedEurope” in which musicians try to fill the European vision with feelings instead of just good arguments.