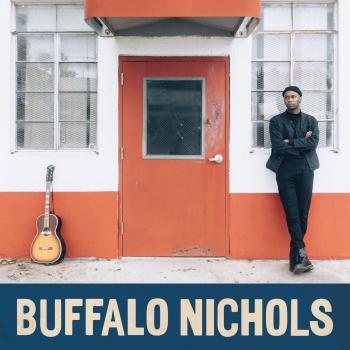

The Fatalist Buffalo Nichols

Album info

Album-Release:

2023

HRA-Release:

15.09.2023

Album including Album cover

- 1Cold Black Stare02:44

- 2You're Gonna Need Somebody on Your Bond03:35

- 3Love Is All03:40

- 4Turn Another Stone03:08

- 5The Difference03:28

- 6The Long Journey Home03:43

- 7The Fatalist Blues02:32

- 8This Moment03:45

Info for The Fatalist

On his second album, The Fatalist, Carl “Buffalo” Nichols does things with the blues that might catch you off guard. There’s 808 programming, chopped up Charley Patton samples, washes of synth. There’s a consideration of the fullness of the sonic stage and the atmospherics of the music that can only come with a long engagement with electronic music. But this is no gimmicky hybrid or attempt to turn the blues into 21st century music by simply dressing it with skittering hi-hats. Nichols’ vision for the blues is of a form of music that’s intimately tied to everyday life in 2023, something that’s reflected not only in the choice of instrumentation, but in the complexities of the songwriting and the gray areas his lyrics explore. This is music that comes straight from the present, and as such, it’s a reminder that the same shit that drove the first blues singers to pick up a guitar is still present behind the throbs of deep bass hits today. The Fatalist sounds unlike any blues record you’re likely to hear in 2023.

Of course, Nichols’ songwriting has always been firmly rooted in the present. He proved he could succeed on the music industry’s own blues terms on his self-titled 2021 debut, whose songs, Bandcamp Daily said, “seem to flow from some great repository of emotion and insight.” The Fatalist finds him digging deeper in search of answers to ever-more-complicated questions around responsibility and self-definition, his plainspoken lyrics both cutting and refreshing in their sincerity and refusal to accept pat solutions. Over a guitar line that blisters and pops with bright sunshine, he holds forth on the simple everyday power of love in “Love is All,” and when he shades his optimism with a clear-eyed view of “bad behavior in the canon of good men,” as he sings, his guitar line goes cloudy with the thought. He slowly walks around a broken relationship in “The Difference,” trying to find the faults. It’s a decidedly modern breakup song, one steeped in moral ambiguity. “I just don’t know the difference between love and sympathy,” he sings, before hoping his once-beloved “won’t forget the one who kept your ego fed.”

Still, Nichols rarely sounds like a blues singer. Like Leonard Cohen, he dominates these songs with his voice. His low, guttural baritone is high in the mix, and he sounds coiled, clenched tight. The slow drip of his songwriting lends The Fatalist an incredible amount of drama, which the production—at times dark and dewy and claustrophobic, at times zippy with light—further emphasizes.

Nichols produced the album himself at home, having recently returned to Milwaukee following a few years in Austin. “Being back in Milwaukee reminded me of why I started making music in the first place. It got me away from the ‘industry-town’ mentality,” he says. “There’s definitely a certain work ethic that comes from being in a city like Milwaukee. There are no clear paths to success and not many examples of ‘making it,’ so people end up creating their own path and developing a broad skill set to sustain a career as an artist.”

That personal touch is evident in how considerately these songs have been framed. “In a lot of ways I was improvising,” he says, and he leaned on his years of experience as a DIY musician—and the songs themselves—to guide him. “Drum machines are a 50-year-old technology. If the blues hadn’t been hijacked and trapped in amber, I think they naturally would’ve been incorporated.” The drum programming throughout feels like a natural rhythmic vehicle for these songs. “When you pick up a guitar, the first thing you’re gonna play is the blues,” he says. “And when you pick up an 808, you’re gonna start doing trap beats.”

The album’s most ambitious song is Nichols’ dusky take on Blind Willie Johnson’s “You’re Gonna Need Somebody On Your Bond.” As he sings of salvation and relief, Nichols creates a soundscape that teems with the joyous claustrophobia of classic gospel. Triggers of Charley Patton’s version connect the earliest blues recordings to the present, both singers’ voices urgent in their message. “It’s important for contemporary musicians to play these old songs sometimes,” Nichols says. “I always keep traditional songs in my set and on my records because I remember how important it was for me to hear somebody interpret a song in a way that made sense to me.”

Nichols further draws the past into the present in “The Fatalist Blues,” a song that simmers with unanswered questions and quotes the classic blues song “Samson and Delilah.” “That was a question that stayed on my mind,” Nichols says. “If you’re raised in a violent environment, are you destined to become that, or can you do something to change that?” The song finds Nichols testing the boundaries of will—“If I had my way I would fill my whole world with love,” he sings, and the implication is he’s not sure if he has his way or not. Even as that ambiguity gives the song a greater sense of dramatic tension, uncertainty also carries within it the glimmer of hope, and the imperative to try.

The stakes throughout this album are largely personal, rather than social; Nichols is singing about his life in the first person, and about his desire to forge his own individuality in a world and a music industry that make it nearly impossible to do so. Ringing through “The Fatalist Blues”—and The Fatalist—is a simple question: Do I have any say in how things are going to go? It’s the question behind so much of the physical and psychic pain in the blues, and in a frustrating age that preaches self-empowerment and shames the disenfranchised, it’s a stridently modern question, too. By playing his music the way he wants to play it, by refusing to give up his creative control or accept anyone else’s definition of the blues or indeed his own life, Carl Nichols has tried to forge an answer. Does he have any say in how things are going to go? Let’s find out.

Carl Nichols, vocals, guitar, banjo, synthesizers, drum programming, percussion

Jess McIntosh, viloin

Buffalo Nichols

Since his earliest infatuations with guitar, Buffalo Nichols has asked himself the same question: How can I bring the blues of the past into the future? After cutting his teeth between a Baptist church and bars in Milwaukee, it was a globetrotting trip through West Africa and Europe during a creative down period that began to reveal the answer.

“Part of my intent, making myself more comfortable with this release, is putting more Black stories into the genres of folk and blues,” guitarist, songwriter, and vocalist Carl “Buffalo” Nichols explains. “Listening to this record, I want more Black people to hear themselves in this music that is truly theirs.” That desire is embodied in his self-titled debut album—Fat Possum’s first solo blues signing in nearly 20 years—composed largely of demos and studio sessions recorded between Wisconsin and Texas.

Born in Houston and raised in Milwaukee’s predominantly Black North end, the guitar was Nichols’ saving grace as a young man. The instrument captured his fascination, and provided him with an outlet for self-expression and discovery in isolation. While other children chased stardom on the field, court, or classroom, Nichols took to his mother and siblings’ music collections, searching feverishly for riffs to pick out on his instrument. Sometimes, this dedication meant listening to a song 200 times in order to wrap his mind around a chord; as a teenager, it even routinely meant staying home from school to get extra practice.

It would’ve required a more than arduous journey across town to find a secular circle to jam with in a city still reeling from redlining and segregation, so despite a lack of a religious upbringing, Nichols went sacred. A friend invited the teenage guitarist to church for a gig and the opportunity proved to be Nichols’ much-needed breakthrough to music circles in the area. But over the following years, he began to feel overextended, and abandoned the demanding grind of a supporting role in nearly ten Milwaukee scene bands, none of which bore his vision as a lead performer. “I was happy with all the stuff that I was doing, and I was learning, but I wasn’t playing anything that was very creatively fulfilling,” Nichols says. “I needed the time and space. I was overwhelmed.”

Stints in college and in the workforce led him overseas, where the appreciation of African-American folkways lit a renewed spark in Nichols. It was the bustling of jazz in places like the working class areas of Ukraine, or in Berlin cafes where expatriate Black Americans routinely treat fans to an enchanting evening of blues, that would lead to his a-ha moment. Nichols returned home to America, meditating on his own place in the music that holds the country’s truest values and rawest emotions between bar and measure. “Before this trip, it was hard for me to find that link between all these blues records I heard and people who are living right now. I figured out it’s not a huge commercial thing, but it still has value. So, I came home and started playing the blues more seriously, doing stuff with just me and my guitar,” Nichols says.

Nichols admits that anger and pain are realities that color the conversations and the autobiographical anecdotes behind his observational, narrative-based approach to songwriting. However, with his lyricism on Buffalo Nichols, he intends to provide a perspective that doesn’t lean heavily into stereotypes, generalizations or microaggressions regarding race, class and culture. The album sees Nichols wrestling with prescient topics, such as empathy and forgiveness on the poignant, ever-building melody of “How to Love;” regret and loss on moving, violin-inflected “These Things;” and the pitfalls of lives lived too close to the edge on the smooth, dynamic “Back on Top.” On the tender, aching album opener and lead single “Lost & Lonesome,” he gives listeners what he describes as a “glimpse into the mind of that traveler looking for a friend and a place to call home;” inspired by his years traveling alone, looking for a place for his passions to fit in, even if temporarily, the track is an ode to exploration and the creative ingenuity of isolation. At the forefront of each song is Nichols’ rich voice and evocative, virtuosic guitar-playing, augmented on half of the nine tracks by a simple, cadent drum line.

While acknowledging the joy, exuberance and triumph contained in the blues, Nichols looks intently at the genre’s origins, which harken back to complicated and dire circumstances for Black Americans. With this in mind, Nichols says there is a missing link, which he’s often used as a compass: Black stories aren’t being told responsibly in the genre anymore. To begin changing that, Buffalo Nichols gets the chance to tell his own story in the right way.

This album contains no booklet.