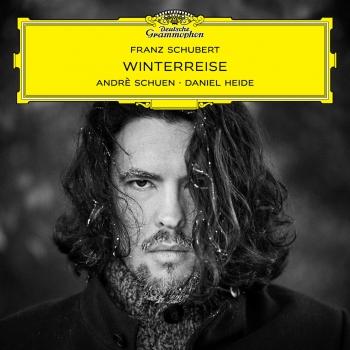

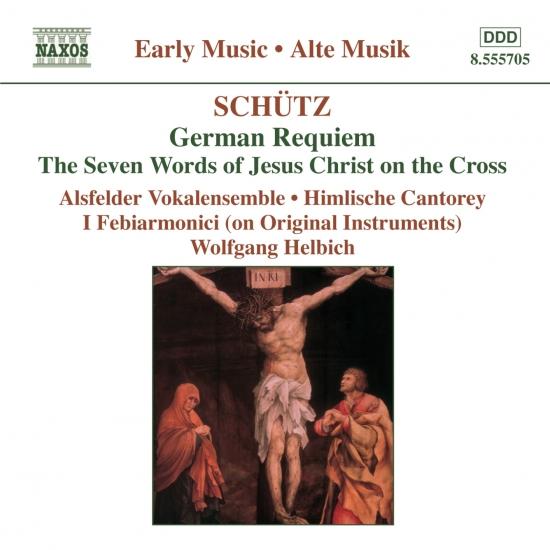

Schütz: German Requiem / Seven Last Words of Christ Wolfgnag Helbich & Himlisch Cantorey Barockorchester

Album info

Album-Release:

2004

HRA-Release:

18.04.2013

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Choral

Artist: Wolfgnag Helbich & Himlisch Cantorey Barockorchester

Composer: Heinrich Schütz

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Musicalisches Exequien (German Requiem), SWV 279-281

- 1Concert in Form einer teutschen Begrabniss Missa03:39

- 2Concert in Form einer teutschen Begrabniss Missa18:32

- 3Motette Herr, wenn ich nur dich habe02:59

- 4Canticum B. Simeonis Herr, nun lassest du deinen Diener03:51

- 5Introitus Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund02:14

- 6Symphonia01:24

- 7Und es war um die dritte Stunde10:44

- 8Symphonia01:23

- 9Conclusio01:33

- Die mit Tranen saen, SWV 378

- 10Die mit Tranen saen, SWV 37803:40

- 11So fahr ich hin zu Jesu Christ, SWV 37902:45

Info for Schütz: German Requiem / Seven Last Words of Christ

The 'Musicalische Exequien' belong to the most famous and most solemn of Schütz's oeuvre. The work was commissioned by Heinrich Posthumus 'the younger' of Reuss-Gera, an educated and cultivated ruler. When he was over sixty he started to make preparations for his death. These preparations included an exact plan specifying what was to happen at the funeral ceremony and in which sequence - including the music to be performed, for which he commissioned Heinrich Schütz.

Schütz's music is not a sort of German protestant version of the Roman Catholic Requiem. In this respect the title of the disc, 'German Requiem', is misleading. It was part of a funeral procedure which was rooted in pre-Reformation tradition of 'exequies' (Lat. exequiae = accompanying a dead person out). They contain three parts: the transfer of the body to the church, the celebration of the Requiem Mass and the procession to the grave.

Being part of a funeral procedure this work could perhaps best be compared with Purcell's Funeral Sentences for Queen Mary.

The three parts are composed in different ways. Part 1 consists of 21 quotations from the Bible and from hymns are set in the form of a German Mass - it says: 'Concert in Form einer teutschen Begräbnis-Missa'. The first section - 'Nacket bin ich von Mutterleibe kommen' - serves as Kyrie, the second - 'Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt' - as Gloria. Here we find a strong connection to the Lutheran 'Missa brevis' (consisting of Kyrie and Gloria only). The quotations from the Bible are set as small sacred concertos (like the 'Kleine Geistliche Konzerte', whose publication Schütz was preparing during the time of his composition of the Musicalische Exequien), the hymns as 6-part motets, to be sung by the 'cappella'. (Schütz doesn't use the chorale melodies as they are still known today.) Part 2 is a bichoral sermon motet, part 3 is a chorus for 5 voices. This section is remarkable in that the first choir (5 voices) should sing the 'Canticum Simeonis' at the organ, whereas the second 'choir', only consisting of three voices (2 sopranos and bass) should sing the text 'Selig sind die Toten' in the crypt, in which Heinrich Posthumus was going to be buried.

In recordings of this work one has to look for other music to fill the remaining space on the disc. Most recordings contain other motets and sacred concertos regarding death. In this case the main other item is Schütz's setting of the seven words of Jesus at the cross. This is perhaps not the most satisfying choice, as this work is not about death in the way the Musicalische Exequien are. One could argue, though, that the most crucial text part of the Musicalische Exequien is that which directly refers to the death and resurrection of Christ as the very foundation of Christian faith: 'Christus ist mein Leben' and 'Siehe, das ist Gottes Lamm' (For me to live is Christ and to die is gain. Behold the lamb of God who beareth the sins of the world).

It is not known when and for which occasion the Seven Words were composed. This piece contains some interesting aspects. The music is relatively simple, and therefore this work was perhaps composed for small chapels lacking professional singers. The work opens and closes with stanzas from the passion hymn 'Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund' (Schütz doesn't use the chorale melody, though), which is also about Jesus's words at the cross. Schütz presents these words in prose, and changes the order of the words as they are referred to in the hymn and brings them in line with the actual order as reported in the gospels. The words of Jesus at the cross are supported by two violins, a practice which was also used by Schütz's pupil Johann Theile and later Johann Sebastian Bach in their respective settings of the Passion according to St Matthew. The words of the Evangelist are given to a solo voice (soprano, alto or tenor), or an ensemble of four voices. This reminds of the practice in Schütz’s Auferstehungshistorie. The piece isn't dramatic, but has a rather meditative character, as the closing stanza indicates: 'Who holds in reverence God's torment and thinks often of the seven words, God will keep him'.

The last two pieces are from the 'Geistliche Chormusik', a collection of motets which was published in 1648. In this Schütz underlines the importance of the traditional polyphony, which he also used in the motet-style parts of the Musicalische Exequien.

The recording is generally enjoyable. I very much admire the performances of the soloists. Their diction and articulation are immaculate, and their declamatory style of singing does full justice to the rhetorical character of these compositions by Schütz, who was always keen to put the text in the centre. The voices are all very clear and blend well.

The choir as such is good, but nevertheless it is the disappointing part of this recording, especially since its sound is rather dense and isn’t as transparent as it should be. The choir is a little too large, and there is too much of a gap between solo voices and choir. The ideal for Schütz's music is a vocal ensemble whose members also sing the solo parts. In that respect Philippe Herreweghe's recording of the Musicalische Exequien (Harmonia mundi) is superior to this one.

The same problem occurs in the Seven Words. The two motets are far more satisfying.

On the whole, though, this is a fine recording which can be recommended. And the music never ceases to impress. (Johan van Veen, www.musicweb-international.com)

'Wolfgang Helbich's array of singers is impressive, fresh-voiced, and responsive to every textual nuance. A splendid album.' (George Pratt, BBC Music Magazine)

Veronik Winter, soprano

Bettina Pahn, soprano

Henning Voss, countertenor

Jan Kobow, temor

Henning Kaiser, tenor

Ralf Grobe, bass

Ulrich Maier, bass

Alsfelder Vokalensemble

Himlisch Cantorey Barockorchester

I Febiarmonici

Wolfgnag Helbich, conductor

Beate Rollecke, organ

Digitally remastered.

The leading German composer of the seventeenth century, Heinrich Schütz lived through one of the most difficult periods in the history of the German lands. He was born in Kostritz, near Gera, in 1585, the son of the former town clerk of Gera, who had taken over the running of the family inn in Kostritz, and his second wife, daughter of the burgomaster of Gera. In 1590 he moved with his family to Weissenfels, where his father later became burgomaster. As a boy Schütz was recruited by the Landgrave of Hessen-Kassel as a chorister, in spite of some opposition from his parents, and had his academic and musical training at Kassel, before entering the University of Marburg. With the encouragement and support of Landgrave Moritz he was able to move to Venice to study with Giovanni Gabrieli, then near the end of his life, remaining there into a fourth year. On Gabrieli's death in 1612 or in the following year he returned to Germany to join the Landgrave's Hofkapelle, while his family did their best to dissuade him from a career as a musician. In 1615, during a period of court mourning at Kassel, he was invited to spend some time at Dresden in the Hofkapelle of the Elector of Saxony, Johann Georg I, in whose service he took on the duties of Kapellmeister, a position he occupied formally from 1619, remaining in Dresden in spite of the repeated attempts of the Landgrave Moritz to persuade the Elector to allow his return to Kassel.

During a long career that brought work in other court musical establishments, when his patron allowed it, Schütz made frequent attempts to secure his retirement from the Dresden court. Nevertheless he was compelled to remain in the service of Johann Georg I until the latter's death in 1657, directing the court Kapelle through periods of extreme privation, as the Thirty Years War, in which Saxony was finally involved, took its course. On his accession the new Elector, Johann Georg II, gave much responsibility to the Italian musicians that he had recruited, while Schütz retained his title, now as principal Kapellmeister, with occasional calls on his services. He moved first to Weissenfels and continued to respond to demands on his abilities from various princely musical establishments with which he had had earlier connections. He returned to Dresden in about 1670 and died there in 1672.

Schütz was a composer of the greatest importance, linking the traditions of Gabrieli's Venice with the music of Protestant Germany. The greater part of his music was in sacred choral works. Here, like Bach and Handel a century later, he provided a synthesis of Italian, Netherlands and German Protestant traditions in a large number of compositions, written during the course of an exceptionally long active life.

Schütz wrote his Musicalische Exequien for the funeral in Gera of Prince Heinrich Posthumus of Reuss, the composer's native region, on 4th February 1636. The music was seemingly at the request of the Prince, who had followed custom by arranging his funeral ceremonies before his death. The work was published in the same year, with a tribute, in verse, to the Prince who was himself a musician of some ability. The first of the three movements has the title Concert in Form einer teutschen Begrabnis-Missa (Concerto in the form of a German Funeral Mass) and is intended for six singers, with organ. These voices can be reinforced by other singers in the sections marked capella, based largely on chorales, which alternate with those for solo voices. It is followed by a motet for eight voices, two choirs, which may be performed unaccompanied. Finally there is a setting of the Nunc dimittis in a movement for two choirs, the second singing the text Selig sind die Toten (Blessed are the dead). Schütz explains in his introduction, that the texts that he sets in the opening section, the first of which correspond to the Kyrie eleison, are those that Prince Heinrich had had inscribed on his sarcophagus. The words of the motet had been chosen by the Prince as a text for his funeral sermon, and the words of the Nunc dimittis had also been the Prince's choice.

Die sieben Wortte unsers lieben Erlosers und Seeligmachers Jesu Christi so Er am Stamm des Heiligen Creutzes gesprochen (The Seven Words of our dear Redeemer and Saviour Jesus Christ that He spoke on the Holy Cross) dates from 1645. At the head of the score are the words:

Lebstu der Weltt, so bistu todt, Und kranckst Christum mit schmertzen, Stirbst'aber in seinen Wunden roth, So lebt er in deim Hertzen.

If you love the world, then you are dead, And wound Christ with pain, But if you die in his red wounds, Then he lives in your heart.

The work, setting the traditional texts drawn from all four evangelists, starts with the Introitus for five voices and continuo, a setting of the first verse of a chorale, avoiding the traditional melody. The following Venetian Symphonia is for five instruments and continuo. The Evangelist, an alto, sings the recitative followed by the words of Christ, sung by the second tenor and accompanied by the two upper instruments and continuo, a procedure that is followed with the later words of Christ. The narrative is continued by the first tenor and the second with the words of Christ to his mother and to his disciple John. The first tenor is followed by the soprano in the continued narrative, leading to the words of the two malefactors, the alto to the right and the bass to the left. The latter addresses Christ, who promises him heaven. Four voices lead to Christ's cry of ¡¥Eli, Eli lama asabthani', which is translated, introduced now by four voices as the Evangelist. The alto provides the narrative link to the words ¡¥I thirst', and the tenor tells of a soldier offering Christ a sponge filled with vinegar and, by a slip of the composer's memory, hyssop, this last the reed of St Mark (a sprig of hyssop in St John). After the final words of Christ, the four voices end the narrative. A Symphonia follows, leading to the final chorale, accompanied, as throughout, by the organ continuo and ending in final contrapuntal writing.

The five-voice setting of verses from Psalm XXVI, Die mit Tranen saen (They that sow in tears), is the tenth of the works included in the Musicalia ad Chorum Sacrum or Geistliche Chor-Musik published in 1648 as Opus 11. This was dedicated to the city fathers of Leipzig and intended, in part, as a model of the older polyphonic style, in particular for the choir of St Thomas in Leipzig and the Thomasschule. The works included seem to reflect a recent controversy, from which Schütz had largely kept away, between Paul Siefert and Marco Scacchi, accused by the former of faulty counterpoint, an alleged Italian failing. Schütz, of course, remembered all too well his rigorous Italian training in counterpoint and the modern style with Giovanni Gabrieli. The first twelve motets in the collection are in five parts, with basso continuo. The eleventh, So fahr ich hin zu Jesu Christ (So onward I go to Jesus Christ), is a setting of the fifth verse of the funeral chorale Wenn mein Stundlein vorhanden ist.